What is the quantified self? (Part 1)

Over the past two years I went from not wearing a watch to always wearing at least 3 (often more) personal trackers that monitor every step I take and every minute of my sleep. And that’s without counting all the apps on my phone.

Why is that? What am I hoping to find in the data? What have I actually learned about myself through self-tracking? Has it improved my life? Is this something you should be doing too?

I’ll try to answer these questions in 3 parts:

- Part 1: What is the quantified self? (you’re reading this)

- Part 2: What has the quantified self helped me learn abut myself?

- Part 3: How do we go from sensors to making sense?

The technology enabled quantified self

It is often said that you can’t improve or manage what you don’t measure. That is why keeping a log of your life isn’t a new idea. People have long used paper diaries to log their diets, activity and schedules. We could call that the paper based quantified self.

Eventually, spreadsheets on computers made it easier than ever to keep a log and analyze the data. We can trace the history of using wearable computers for self-tracking back to the 1970s, when computers were still expensive, big, and mostly in the domain of university labs.

The term quantified self was coined in 2007 by Wired editors Gary Wolf and Kevin Kelly with the tagline “Self-knowledge through numbers”. Around that time, inexpensive pedometers and other sensors were starting to appear on the market, along with websites that made it easy to capture and analyze all sorts of inputs.

2007 was also the year when the iPhone was introduced, which made powerful mobile computers both cool and easy to use. As smartphones started taking over the world, all sorts of sensors have gotten cheap and small enough to be embedded into our smartphones. It’s also become easier than ever to develop web and mobile apps that help you keep track of various aspects of your life: health, fitness, productivity, finance, … You name it. There’s probably an app for that already out there.

The sensors that are quantifying your life

In terms of hardware, interest in self-tracking has been recently popularized by inexpensive wearable sensors (wearables) that are often worn on our wrists. Most of these wearables use an accelerometer to count the number of steps you take and to monitor how restless you are during your sleep.

More expensive personal wearables often include an altimeter sensor to count the number of floors you climb and a heart rate sensor for improved fitness monitoring. Most modern wearables sync directly with your smartphone. Some have small screens to display things like time, current step count and notifications, while others rely on simple light (LED) status indicators. It’s common for wearables to include vibrating alarms and alerts, such as gentle nudges that remind you to take a break if you’ve been sitting idle for too long during the day.

One of the best known companies in this space is Fitbit, which now offers anything from a simple step tracker that clips onto your clothes to GPS watches that monitor your heart rate in real-time, and everything in between. Fitbit is currently still the most popular wearable maker, with its market share in Q3 2015 estimated at around 22%, followed by Apple with 19%, and the Chinese Xiaomi at around 17%.

The cost of basic personal wearables is usually around 99 USD, but you can also get entry level trackers like the Xiaomi Mi Band for less than 20 USD. That’s cheaper than a gym membership, so it’s pretty easy to rationalize as an investment into one’s own health. (Even though, like gym memberships, a lot of wearables end up collecting dust after a few months.)

Smartphones made wearables very easy to use. Getting activity data from your wearable onto your phone is fast and hassle free thanks to Bluetooth Low Energy. It can even happen automatically in the background. No cables required.

With sensors getting smaller, cheaper and less power hungry, they became a perfect fit not just for wearable bracelets, but also smartphones. If you have a newer smartphone, there is already a fitness tracker in your pocket. A lot of smartphones optimize the way data is collected, so they can count your steps in the background without significantly draining the battery. A fitness app was likely preloaded on your phone, alongside email, a web browser, music player and other modern essentials.

And now watches, the original wrist technology, also want to make you healthier. Modern smartwatches like Pebble, Apple Watch or those based on Android Wear, all come with a promise of improved fitness thanks to built-in accelerometers for step counting. Even traditional mechanical watches are trying to compete. From the relatively inexpensive newcomer Withings with its Activité range, to expensive Swiss watch makers.

With activity tracking no longer in the domain of sports fanatics and worn all day long, the way a wearable looks and feels is increasingly important. You don’t want something you wear at the office or at a dinner party to look like a sports gadget. Wearables are becoming a fashion accessory. Those targeted at women even describe themselves as jewelry.

The apps that want to improve your life

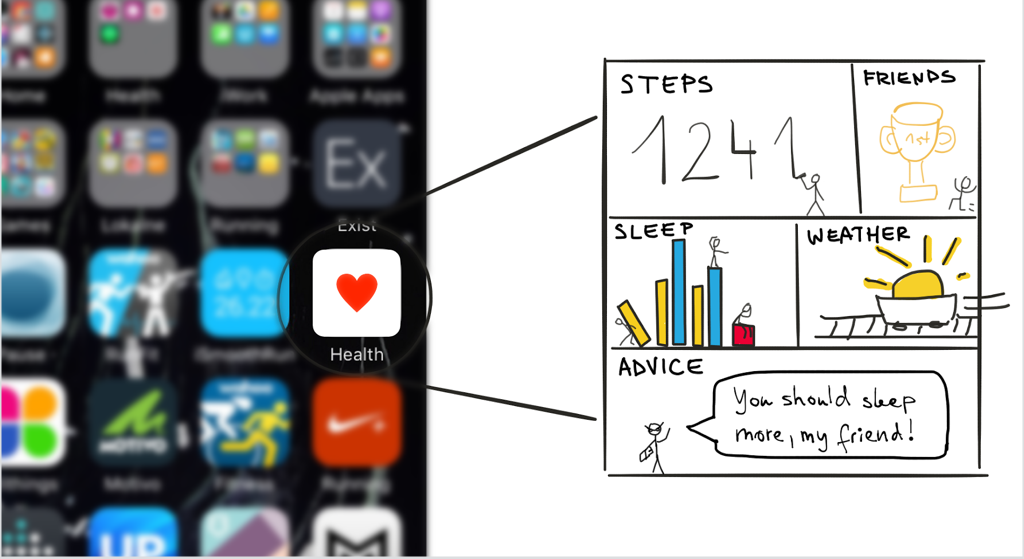

But of course, collecting data and looking good while doing it is just one part of the equation. The other is the software that aims to make the collected data useful and also allows us to track parts of our lives that can’t be easily collected by wearables.

These days most wearables are paired with a companion smartphone app that makes it easy to sync collected data into the cloud. This makes it possible to visualize data over time and even provide useful advice.

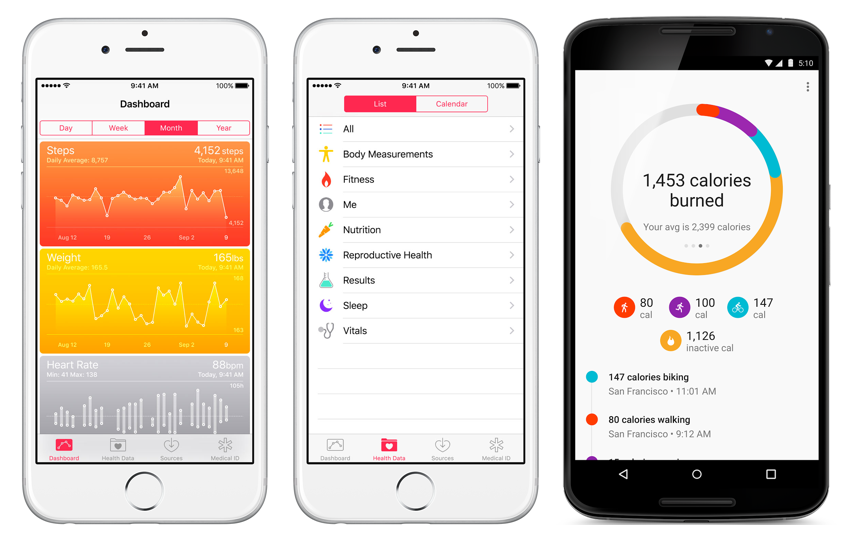

If you use wearables and accessories from different companies, it’s annoying to have a separate app for each of the things you’re tracking. App developers can use APIs from other apps to pull in missing data into their own apps. But with the number of available data sources increasing, it was clear we also needed tools that can make apps work together.

IFTTT, the recipe based tool for connecting apps, was one of the earliest tools that made it easy to, for instance, feed Withings weight data into the Fitbit app (or the other way around). Now both Apple and Google have this functionality built into their mobile operating systems with Apple’s Health and Google Fit respectively. (And there’s even Microsoft Health.) Apple is even promising to power the future of medical research with ResearchKit. Health as a service could become a great market for these software giants.

Meanwhile, developers can create apps that combine data from different sources and provide better insights in return. Without even requiring custom hardware wearables. Jawbone, for instance, offers two apps for health and fitness: one that requires Jawbone’s physical UP wearables, and the other that uses the data from your phone and supports manual tracking. Both offer Smart Coach, an intelligent guide with personalized advice that encourages you to be more active or sleep better.

App stores are also packed with apps that support manual tracking of things that can’t be easily captured by sensors yet. There are countless apps for tracking mood, food intake, books read, personal finance, productivity, and almost everything else you can think of. The benefit of using an app for this kind of tracking is that you have a complete history of your activity, easily searchable and ready to be analyzed. Unlike paper journals, smartphones can also remind you to log your progress by regularly nudging you with push notifications.

These apps are not restricted to just our smartphones, of course. There are desktop apps like RescueTime that can automatically log your computer time and provide detailed activity and productivity reports each day. And of course a lot of journaling and logging apps also have desktop versions or live in your web browser across multiple devices, even on your TV.

Regardless of how you log your data, everything is synced with the cloud in real-time. No need to worry about backups, your life is now in instant sync across devices. The big questions remains though: how useful is this data?

Your smartphone is already tracking you. Will this really make you healthier?

As we’ve seen, the technology for self-tracking has gotten so small and ubiquitous that it’s already in your smartphone, whether you want your steps counted or not. Your smartphone also knows where you are, and it’s just a matter of time before it gets additional sensors that will be able to quantify even more aspects of your life. The same is happening to other personal objects in your life: watches, TVs, cars, your home.

Quantified self could soon become just something all your “things” do for you, so you might as well get something useful out of it. But can all this data really make you healthier, more productive, even happier?

We’re definitely still limited by what we can track about ourselves, either automatically or manually. Certain aspects of our lives are just not easy to quantify. And you need consistency in your self-tracking to get meaningful results, all the while the benefits aren’t yet fully clear beside the general “you’ll be healthier if you move more and sleep well”.

The data we willingly collect about ourselves can certainly be used to find out more about habits of people in different parts of the world, but large scale scientific experiments are still difficult due to different tools and approaches being used in self-tracking. Add to that the possibility of the Hawthorne effect that could lead you to changing your own behavior just because you’re being observed or the fear that having all this data just contributes to increased stress of “not living up to your potential”. Not to mention the privacy and security concerns.

Some skepticism is certainly in order. At this point you might also be wondering: what have I learned so far by surrounding myself with sensors? Head over to Part 2 as I explore my own reasons and approach to self-tracking and try to figure out what self-tracking apps and tools need to become truly useful!