How do we go from sensors to making sense? (Part 3)

There is no escaping sensors that monitor your activity. They’re already in your smartphone and slowly taking over our buildings, cars and more. And there are countless apps that can help you monitor everything that isn’t already automatically tracked by your smartphone.

It’s never been easier to quantify your life. Unfortunately, as already hinted at in the overview of the quantified self movement in Part 1 and my own personal experience in Part 2, the benefits of self-tracking are still less clear other than the general “know how many steps you take”.

Even I haven’t yet been able to get much further than that with my small army of trackers. But I still think we’ll start discovering more benefits in the next couple of years. Sensors on our bodies and in the spaces we inhabit will help us improve our health, well-being and productivity once we figure out how to use them a meaningful way. They are probably even the future of medicine.

What we need before we reach that point though are better tools that provide a clearer value to their users. Here are some thoughts on how we might make that happen.

Paying attention to context and finding the right carrot or stick

Firstly, self-tracking tools need to become more aware of a person’s context. Location data and a person’s schedule are good starting points, but things are often more nuanced. Is the human you’re monitoring taking a day off to relax and exercise or because they are injured and unable to leave home? That’s a big difference that current apps just ignore.

Instead of being supportive personal trainers, they treat us all as robots with no feelings. They see us as black boxes that need 10,000 steps and 7–8 hours of sleep each and every day. No exceptions. Very low on the Maslow hierarchy of needs.

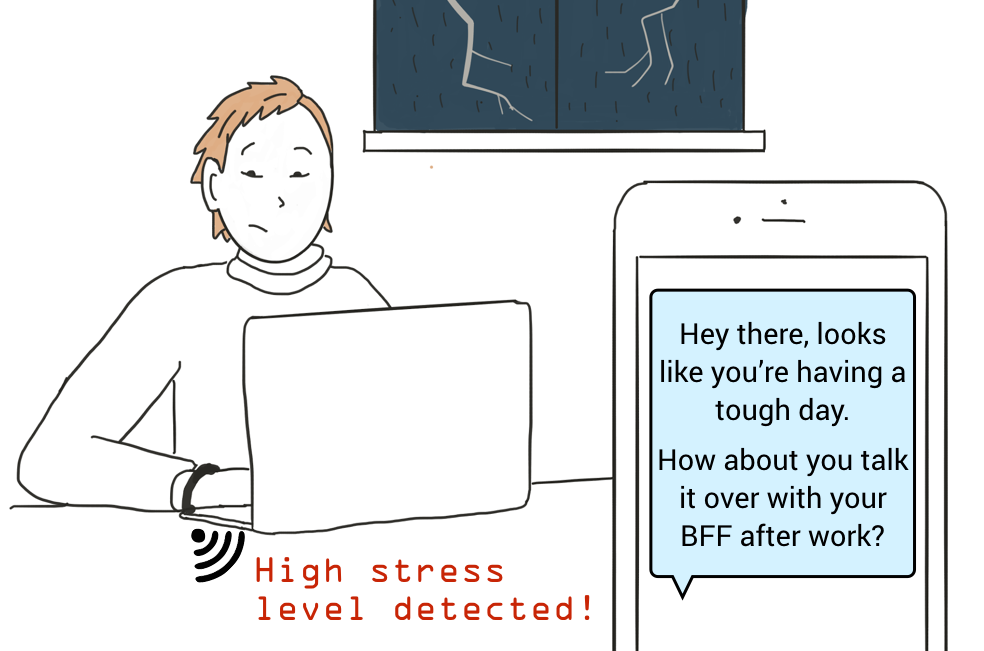

The “kick in the ass” tone of “encouragement” most apps use isn’t always the best approach to get a person moving. A suggestion to schedule time with friends could be more beneficial to someone who’s overworked or depressed. Health isn’t just about the number of steps you take, it’s also about the experiences you have.

Which is why I’m increasingly interested in the idea of a wearable tracker that monitors feelings. If the device can detect that I’m stressed, maybe it’s not the right time to make me feel bad about my low step count. There’s a difference between suggesting a walk as a way to relax and guilt tripping me into a walk.

This is what everyone building self-tracking tools should keep in mind. When you don’t take personal circumstances into account, you end up becoming an annoying distraction and eventually lose the user. You fail to provide value, and the user loses their trust — rightly so.

Getting devices to talk to each other, not just comparing scores

The context problem could partially be solved by devices and apps talking to each other in more meaningful ways. For instance, if I’ve just checked-in at an airport, don’t make me feel bad about the lack of exercise or sleep. I probably won’t go back to my usual routine until I get back home.

The lack of meaningful communication often results in annoying push notifications that appear on our smartphones at the worst possible times. When I’m busy writing, I don’t want to be disturbed by a notification telling me I should go for a walk. The same notification would, however, be more relevant when I open Facebook because I’m in a need of a mental break.

Ok, I understand it’s difficult to get different products to play nicely with each other. But why aren’t devices from the same maker working together?

Take for instance Fitbit, a company with one of the largest self-tracking communities in the world. You can compete with friends in activity challenges and compare your activity and sleep habits with your own age group worldwide. But the Fitbits are not at all aware of each other. My Fitbit app could detect when I’m hanging out with one of my Fitbit friends, in person. Wouldn’t it be interesting to see how that friend affects my mood and behavior? Am I more active when I hang out with friends? Or do I get less sleep? Also, when I’m hanging out with friends, it’s probably not the best time to send me notifications of any kind.

(Fun tip: Open a Bluetooth finder on your smartphone at a conference, you’ll see how many Fitbits and other wearables are around you.)

The current situation with sensors reminds me of personal computers back in the 80s. They were perceived as toys for geeks, something that could only be used to play silly games. It took time for us to find powerful use cases. And of course, we unleashed a revolution when we started connecting computers into networks, enabling people to communicate and collaborate online.

I believe the same is needed for sensors. On their own, they’re kinda cool and fun, but we’ll start exploring their real potential once they start talking to each other. Call it the Internet of Things or whatever you like.

From quantified self to quantified us

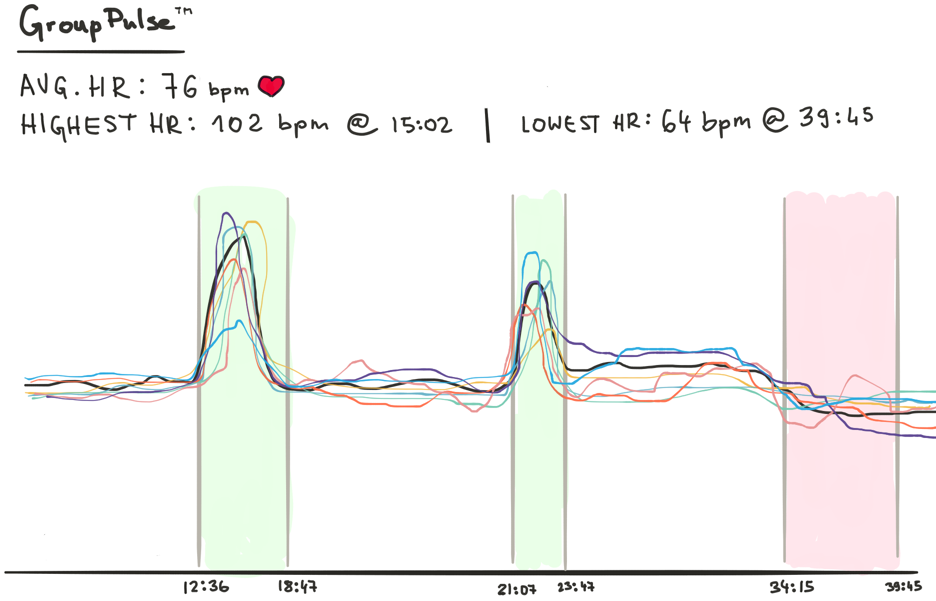

Once you have things and sensors talking to each other, you can also discover interesting things about people sharing a space or an experience. Recently, a couple of DJs attached heart rate monitors to a few fans to see when the music they were playing made the fans’ hearts beat faster. The results are fascinating.

I think it would be similarly interesting to collect data from people sharing a virtual experience. People watching the latest SpaceX launch online. A group raiding together in a MMO (massively multiplayer online game).

The ability to directly monitor your audience’s physical responses could become an interesting and inexpensive tool for the entertainment industry. You could easily beta test your game or movie around the world to see how exciting it is. Wanna bet this will become a big deal in upcoming virtual reality (VR) content? I’ll be surprised if heart rate monitoring doesn’t become a standard feature of VR headsets in a couple of years, as prices drop.

And while using sensors to gauge the crowd’s reaction to your music performance or game might sound frivolous, imagine that in other group settings. A classroom. A meeting.

How stressed are your students? How well does your team get along? How do meetings affect productivity? How are astronauts really dealing with stress on long duration space missions (which will hopefully become a big thing in the future)?

From quantified people to quantified spaces

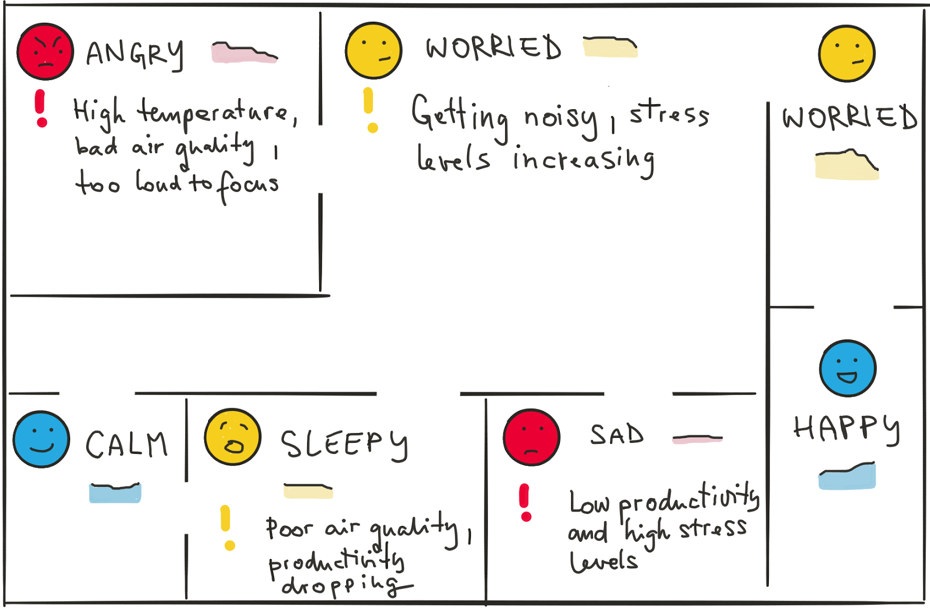

Speaking of groups in shared spaces, I also think a lot can be discovered with better environmental monitoring. Not just whether the environment in our homes is healthy or productive at our offices. Think about being able to detect laughter, do real-time voice stress analysis, quantify the amount and quality of communication in a room. You could tell a lot about how teams get along without requiring individual monitoring.

If you could feed all this information onto your own personal dashboard, you could also see how spending time in certain places, with certain people affects your well-being. Is the air quality in your city making you sick? Are you unhappy if you don’t spend enough time with your friends or if you don’t get enough alone time? Is your job making you miserable?

Self-tracking or mass surveillance?

As the world becomes more connected and the amount of available data grows, the question of who owns the data and how to guarantee user privacy and safety will become increasingly important. Especially when we start connecting data from different sources. It’s important for users to remain in control and be aware of how and with whom their data might be shared. Even if it’s being anonymized and aggregated.

Even with our current trackers having relatively limited reach, we’ve already seen hacks that range from slightly embarrassing to having more serious implications. For instance, a few years ago a bad design decision made it possible to search for Fitbit users who logged their sexual activity through the service. And there’s already cases of Fitbit logs being used in courts to dispute false claims. Who needs Big Brother if we’re willing putting ourselves under surveillance?

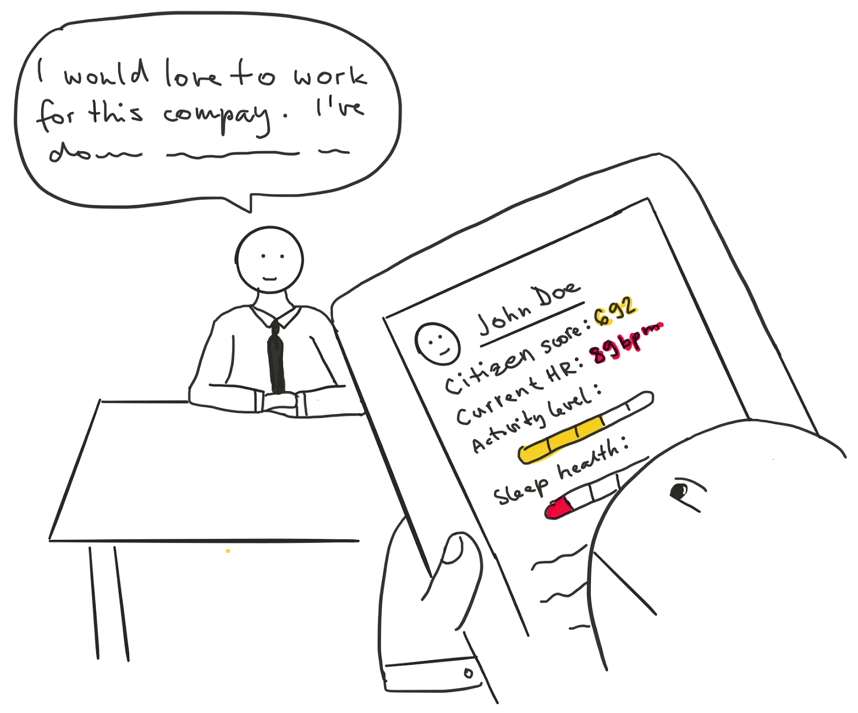

The question of who has access to your data is a big one. Can your insurance company penalize you for not being active enough? Can your boss track your productivity and activity, even outside of the workplace?

Companies are already monetizing their self-tracking software and hardware through “corporate wellness” programs. Fitbit Wellness, Jawbone Wellness, Withings Corporate Wellness 360°, Misfit Enterprise … All in the name of improved health and productivity, right?

And what if your country wants to access your data too? China is already developing a Social Credit System (SCS) that calculates citizen’s personal scores based on purchases and activity on social networks. Once that system is in place, it won’t be difficult to add activity and sleep data. Reward citizens for being more active, penalize them for sleeping in. Feeling uncomfortable yet?

From wearables to implantables and ingestables

And if you don’t like the idea of your boss or insurance company knowing your step count, it could get even more uncomfortable as we move from wearable to implantable sensors that become part of our bodies. Or ingestible sensors that you take with your pills.

It might sound like science fiction, but we’re not far from that future. Here are just some examples of next generation personal sensors that are already being tested:

- smart pills that talk to your smartphone and monitor the effect a certain medicine or even diet have on your body

- implantable chips that replace your ID

- wearables that read your mind and act as brain-computer interfaces

Sensor-based future of medicine

And there’s Google’s glucose-measuring contact lens, which is now being developed as part of Verily, the life science arm of Alphabet. Take a look at their intro video on YouTube for a feel of what’s coming.

Hardware and software meet the human body. Highly personalized, based on direct monitoring, sending data to your doctor in real-time. While a lot of doctors still frown upon the data collected by fitness trackers, some are already beginning to see their benefits. There’s already a famous case of Apple Watch’s heart rate monitoring saving a teen’s life.

While that might sound like a lucky coincidence, I do think we’ll be seeing more benefits of highly personalized health monitoring. Once you can directly monitor what your body is doing, you can also have implants that help you maintain a healthy balance without you even knowing. There are countless applications that could significantly improve life quality of people with chronic diseases, disabilities, and even prevent illness.

Privacy, security and data ownership need to become a big deal

While the benefits are potentially huge, this kind of personalized, embedded technology opens even bigger ethical discussions on top of some very serious privacy and security concerns. Right now, you can always take a wearable off, leave your phone at home when you don’t want to be tracked. But what do you do once the thing tracking you is inside your body?

You think somebody hacking your Fitbit is scary? Think of somebody hacking into your body and disabling an implant that is keeping you alive.

Those developing tools for self-tracking will have to be even more conscious of privacy, ethical and security concerns. Companies should set defaults that protect the users and invest in the development of robust systems that won’t be easily hackable, which is unfortunately the case with many Internet of Things devices on the market right now. Stories about hacked baby monitors and dolls are doing a great job at scaring off consumers.

It’s not just the underfunded startups being careless. Big companies are making the same mistakes. Security, privacy and data ownership are industry-wide problems that we all need to take more seriously.

“Just listen to your body”?

With all these big concerns emerging as our self-tracking technology develops, the voices of skeptics will probably get louder. One common argument is that we don’t need all of these sensors because our bodies supposedly know best. We should just listen to our bodies more if we want to live healthy and long lives.

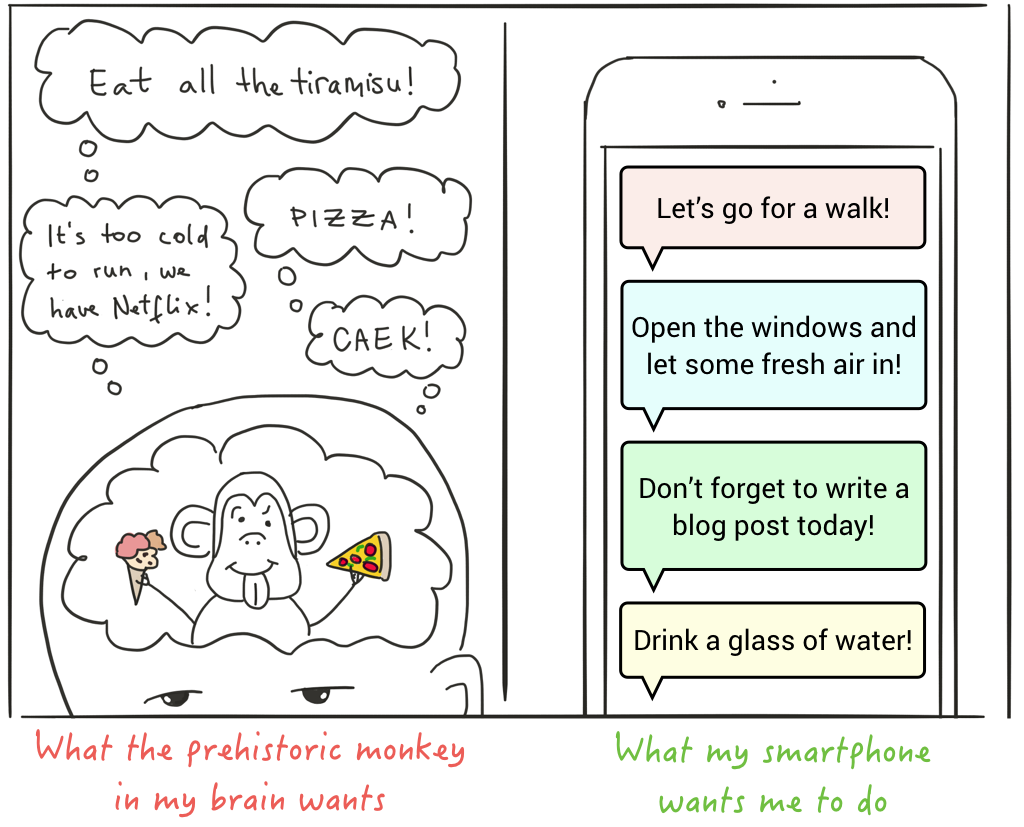

Well, our bodies evolved in times when eating as much as you could was a good strategy, as you were never sure when the next meal would come. Our sweet tooth was developed because sweeter fruit offered more energy, but then we invented chocolate (not fair!). And our bodies don’t like wasting energy, so the muscles you don’t use are happy to deteriorate (have fun getting them back!). And we have many other wonderful gifts like that from ancient times.

So, if you have a finely tuned body that is giving you the right signals, well done! Mine is telling me to eat all the tiramisu at once and not to go run outside because it’s cold. So I take every little bit of encouragement I can get to make myself run because it’s supposed to be good for me.

I don’t expect technology to solve all my problems and make decisions for me. But I embrace the idea of a friendly and helpful personal assistant that provides timely and useful advice. Like reminding me to eat or to turn on the light when I get so absorbed in work that I forget my surroundings.

Do I need to wear several personal trackers for that to happen? Probably not. And neither do you. But I do think this is the beginning of something important, which is why I’m trying to learn as much as I can about the available tools and what they can offer me. At the same time, I do think it’s important to talk about the potentially dangerous (ab)uses of personal tracking technologies, especially as they become one with our bodies.

This isn’t just something that will go away if we ignore it. Some wearables might be a fad, but sensors are here to stay. That’s why I think now is a good time to learn about their potential. If you want to learn more about self-tracking as well, you can easily start with your existing smartphone or an inexpensive sensor and see whether you get anything useful out of it.

P.S.: If you haven’t already, check out Part 1 of this series for an overview of the quantified self movement and Part 2 to read about my own personal experience with self-tracking.

Tags:

Tags: