What has the quantified self helped me learn abut myself? (Part 2)

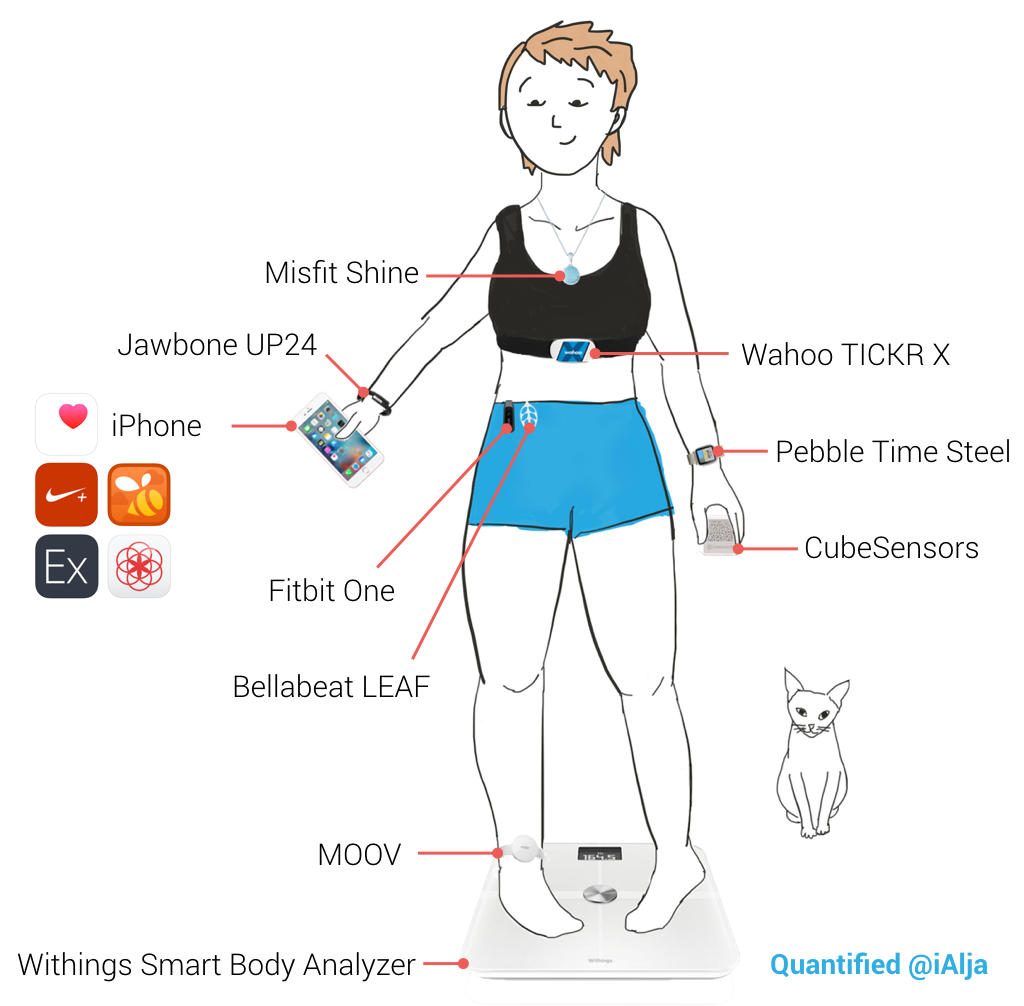

I know exactly how many steps I’ve taken in the past 938 days. And how many hours I’ve slept on each of those nights. If fact, I can compare measurements from multiple sources for a lot of these days, as I‘m currently wearing at least 3 personal trackers at all times (not counting my smartphone here). The list of tools I use was actuallys so long that I’ve decided to turn it into a separate post.

What is the goal of all this self-tracking? And what have I learned by counting my steps, monitoring my sleep and more?

These are the questions I’ll try to answer through this post. If you’re new to the idea of the quantified self and self-tracking tools, you might also want to check out Part 1.

Why do I track different aspects of my life?

It all started with running

The beginning of my self-tracking dates back over 5 years ago when I was completely out of shape and decided to start running again. I bought new running shoes and the Nike+ shoe sensor that was compatible with my iPod. After a long period of inactivity, I wanted a tool that would keep me motivated and that would allow me to track my progress over time.

And it worked for me. I reviewed my running stats after each run, celebrated big milestones. And I eventually upgraded to the Nike+ GPS Watch as soon as it came out and I was training for my first half-marathon. In fact, the motivational factor was so great that it partially led to overtraining and injuries (but that’s a story for another time).

Moving to 24/7 tracking

So, my initial goal was to get fit and healthier through running. What got me interested in a fitness tracker that I’d wear all day was the idea of tracking sleep. How much sleep do I actually get on average? I feel like I didn’t get any sleep at all last night, is this true?

To answer these questions, I started wearing Fitbit One day and night in the summer of 2013. And discovered that my sleep wasn’t all that bad, even though I am often restless during the night. I also discovered competing with friends in the weekly step leaderboard can encourage me to be more active. (Note: the competitive encouragement doesn’t work so well during winter, when it’s super cold outside.)

Around that time, I also started working in an hardware startup and I became curious about differences between trackers and how they attempt to make sense of the data they collect. So part of it was for research purposes, to experience first hand how different trackers affect me. How comfortable are they? How annoying is the weekly charging? How useful is each app?

Asking the big questions beyond real-time tracking

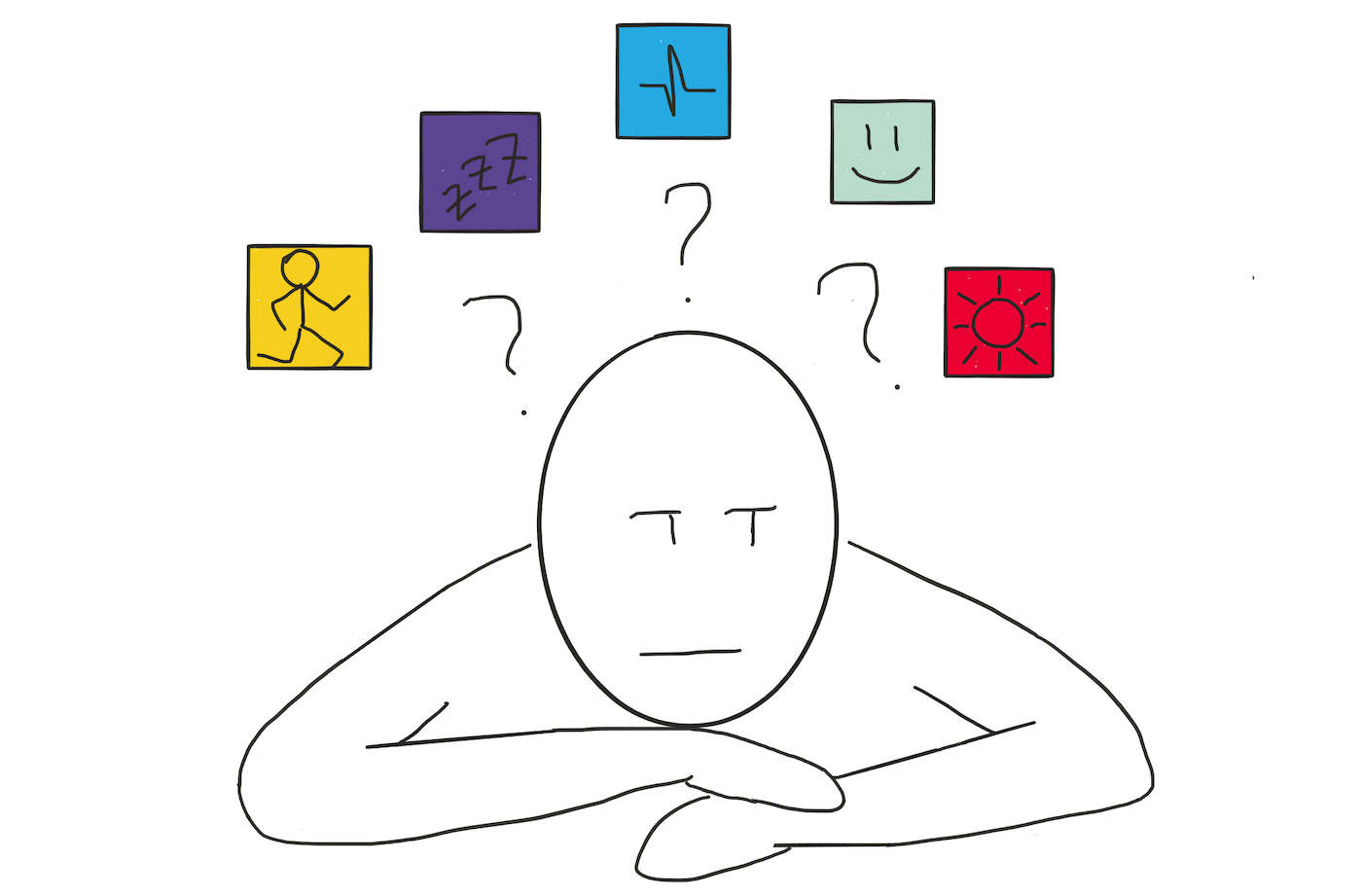

In time, as my collection of trackers grew, I become interested in finding patterns in the growing amounts of data I have been collecting. Knowing how active I am and how well I sleep is cool, but does sleeping bad make me less or more active? Or, for instance, does bad air quality affect my sleep? How does weather affect my productivity? And so on.

When I mention all the things I track, I often hear comments like: “I don’t need a tracker, I know how I active I was today” or “I know whether it’s warm enough at home”. True, you might be aware that you walked more than usually because your feet hurt. Or you know that the temperature is just right because you don’t need to put your sweater on. But we’re usually not very realistic in our own estimates.

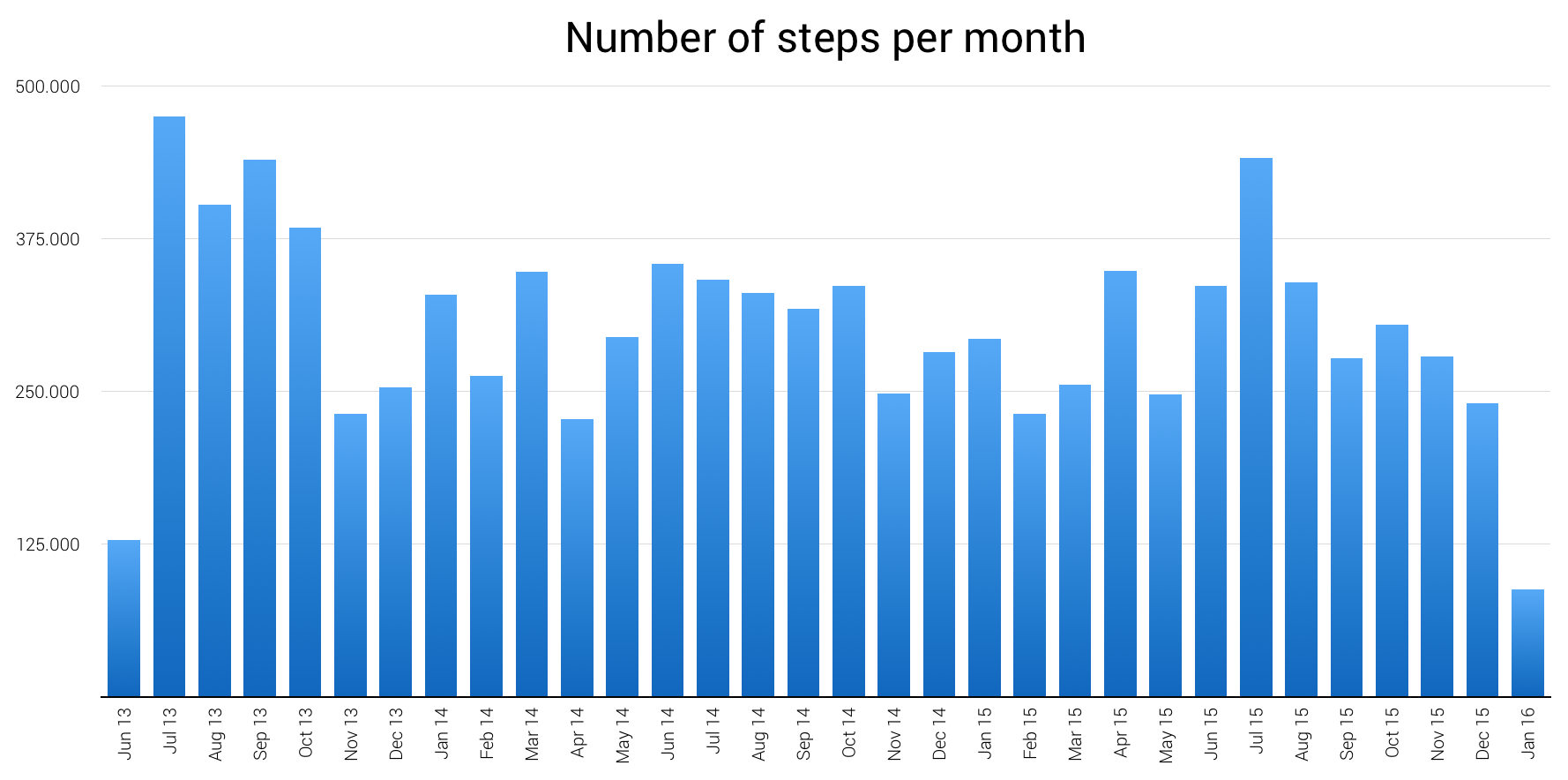

You probably underestimate the time you spend on Facebook every day (I dare you to start tracking it). And overestimate the time you’re awake during the night (almost all of my friends that tried sleep tracking came to the same conclusion). And we’re certainly bad at comparing these vague estimates over time. Which is why it’s useful to have an objective log for comparison. Even if the step count of a particular tracker isn’t super accurate, you can compare its data over time to see patterns.

That is why I’m increasingly looking for services that offer export capabilities or APIs that make it possible for app developers to include data into their own services. The number of steps you took today is an interesting measurement. But discovering how the amount of steps changes over the year when compared to your calendar, weather, sleep or more can help you make better choices.

So, what have I learned about myself?

Since June 2013, I took 9,676,213 steps and climbed 13,153 floors. My lifetime daily step average is 10,382. Recently I’ve only been averaging 6615 daily steps. I spend on average 434 minutes asleep each night. It takes me on average of 12 minutes to fall asleep and I have an average 91% sleep efficiency.

But that’s just the numbers. Here’s some of the other things I discoverd about myself by digging through the collected data:

- Weight increases can be mapped to important milestones/deadlines at work. Note to self: should avoid chocolate during busy times.

- When I feel like I haven’t gotten any sleep during the night, I actually do spend most of the night sleeping, I just have more awake times. Note to self: don’t worry about falling asleep, it will eventually happen.

- I was able to start going to bed a bit earlier by setting up a “Prepare for bed” reminder on my wrist-worn wearables. Note to self: set the reminder about 30 minutes before you actually want to go to bed.

- Maintaining the recommended humidity level at home makes me feel and sleep better, especially during winter. Note to self: keep a humidifier running most of the winter and use the dry mode on the AC during summer to lower the humidity when needed.

And … yep, that’s pretty much it. No major life changing insights yet. But as already mentioned, there’s also the benefit of having daily measurements available and feeling the shame of finishing last in the weekly steps scoreboard.

What’s missing?

One of the big limitations of self-tracking gadgets and apps in general is that they’re still surprisingly unaware of their context. There’s nothing more annoying than an app trying to get me to run while I’m lying home sick or injured. That’s what I call rubbing salt into the wound.

Part of the problem is that a lot of self-tracking apps are screaming for attention when they have nothing to say. A push notification can be useful when sent at the right time, but most apps settle for sharing trivia. Ok, so I took 78.574 steps last week. Is this good? Do I need to know this now?

More often than not, these notifications just end up being a distraction or stress us out. Apps should only disturb us when they have some valuable advice for us and when that advice can be most effective. Look, I’m not going out for a run at 11PM while I’m getting ready for bed just to reach my daily step goal, ok?

The annoying push notifications and bad timing are also a big hurdle for apps that require manual tracking. These apps regularly nudge you to log your mood, meals and similar at set times or intervals. They rely purely on your ability to consistently and reliably log your activities. I don’t know about you, but counting calories takes all the fun out of eating for me. Similarly, mood tracking apps just end up annoying me because they ask me to talk about my feelings at the wrong times of the day.

This has led me to the conclusion that the most effective tracking happens automatically, in the background. A good example is my smart scale: I just have to remember to step on it in the morning, but once I do, it takes care of everything else on its own. It doesn’t get too upset if I skip a few days while traveling. And it syncs all measurements into the cloud, where they wait for me until I have time to review them.

But reviewing all these apps also feels like a chore. It’s clear that we need better tools that will help us make better sense of the data. Right now, the most useful aggregator app I’ve found is Exist, but it doesn’t yet support all the data sources that are important for me and a lot of the correlations it points out are obvious. For instance, I do know that I get up later and sleep more during the weekend (doh!). It would be more useful to see if I sleep in more when I’m stressed out during the week or when I run more.

It’s funny how all the big software giants are competing to get our data, but few are helping us discover meaningful patterns and offer advice in return.

For more on how we could make sense of all the sensors that are tracking us, head over to Part 3. You can also go back to Part 1 for an overview of the quantified self movement and the hardware and software fueling it, or check out my short reviews of the tools I use for self-tracking.

Tags:

Tags: